The Search For Julia – Part II

On 11 February 2022 by TRaymond(I promise, no cheesy shoe metaphors this time!)

So, as I shared in The Search For Julia, one of the projects I’m currently working on is trying to track down the lineage of my 3rd great-grandmother, Julia Light.

Julia was born in 1819/20 somewhere in Maine. Unfortunately, I have yet to find a copy of the marriage record for when she married Abraham Place, so no information can be garnered there. Also, I am having a field day of a time trying to find vital records for the town that she was married in prior to 1855, and given that she was born in 1819/20, there’s a good chance Julia was married sometime in the late 1840s.

To make things more interesting, the US Census information for the era in which Julia was born isn’t always as helpful as it could be.

Prior to 1850, the US Census only recorded heads of household, typically men, and no other names. (Every now and again a widow, single mother, or spinster would show up on the census, but sometimes even these names would be erased from history and the eldest white male would be names head of household instead of the true, female head of household.)

In order to find someone born in 1819/20 of which the parents are unknown, there is a long process involving census records – especially in Julia’s case as I have yet to find a birth certificate either. This process is where the 52 Ancestor prompt comes into play. When people mention “Branching Out” in genealogy, many thing of going out onto the branches of the family tree, to cousins, aunts, uncles, etc. My mind tends to take that one step farther and I find myself branching into communities, states, and regions.

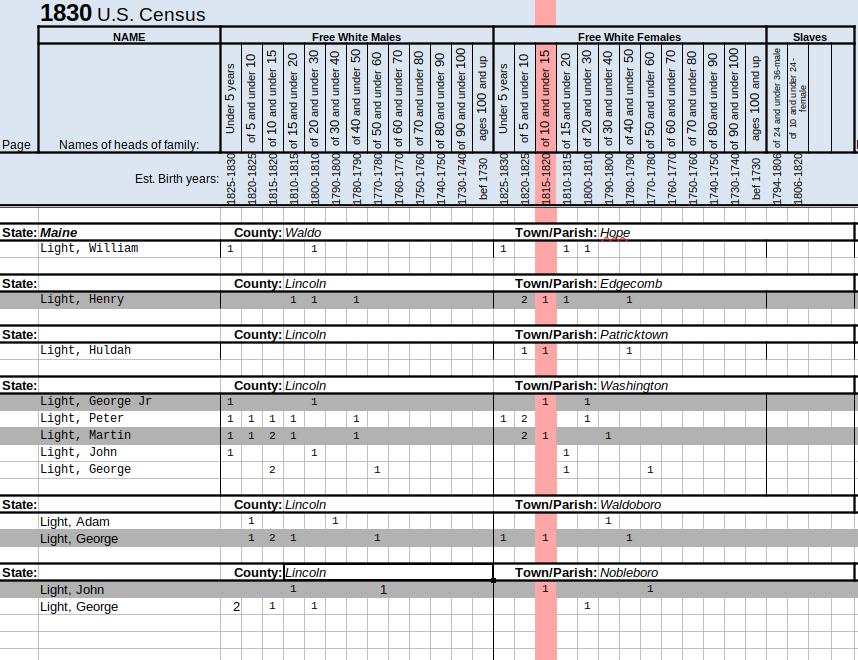

With Julia, this is the path I took: I decided to start branching out into the state as a whole, knowing that the population of Maine at the time of her birth wasn’t that far spread. Taking her estimated age of birth from the 1850s census records, I began looking at households where she would have lived as a teenager. I look through the 1830s census records for entries of young females “of 10 and under 15” years of age.

It needs to be noted that I don’t look at just the census listings for the town that Julia later resided in, Patrickstown Plantation (later known as Somerville), but across the state, as I can find no solid information placing her birth in Patrickstown Plantation. I look at all census records with the same last surname and others that could be a misspelling of the surname. To me, this is like looking up into the canopy of the woods and trying to find the branches of a specific tree. There are so many inter-crossing branches that it’s hard to trace, unless you can take a picture of just those branches and work to trace them back to the trunk.

I gather together the information into a well designed mockery of the actual 1830 census forms.

This allows me to do two things: 1) I can have a better idea as to whether Julia was born in Maine – after all, if I find no families with the same name, then there’s a good chance she was born elsewhere. – and 2) I can more easily find the families that Julia may have been a part of.

Once I can see the families with a young female of the right age, I can then look at the 1840 census data and compare to see which of these young ladies are no longed part of the family. Given that Julia’s oldest child was born in 1837, she would most likely not be living with her parents.

The step after that? Tracing each branch of the same species of tree back to see if I can find the trunk. I’ll be looking at each individual head of household with a young female of the right age listed in the 1830 census but gone in the 1840 census. The hope is that one of these branches will lead to the “trunk,” to the family that Julia was born into.

This blog post is done in part for Amy Johnson Crow’s #52Ancestors challenge. To learn more, visit https://www.amyjohnsoncrow.com/52-ancestors-in-52-weeks/.

Active member of: