One of the prompts in the #52Ancestors challenge had to do with “courting.” Partakers were given the ability to decide what form of “courting” they wanted to look on, whether it be court documents and the like or romantic courting. I decided to hit a bit of a middle road: courting when post-courting goes array.

One of my 3rd great-grandmothers up my maternal line is a fantastic example of this myth that many of us modern day folk have bought into for a long time. When you bring up the concept of divorce in American culture, many make the mistake of thinking that this is a relatively new thing. For sure, divorce rates have climbed since the 1980s, but divorce is something that happen pretty regularly even in the early 1900s.

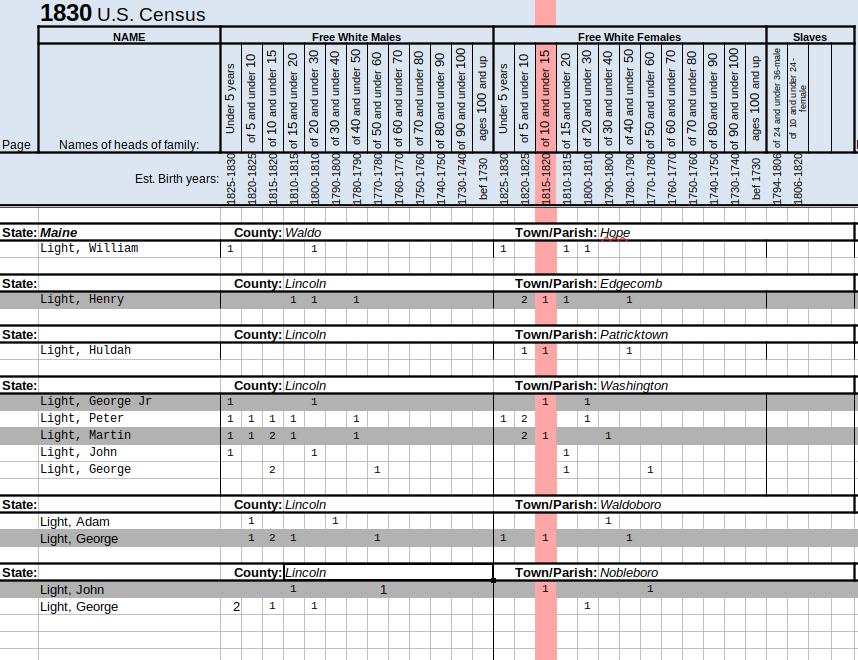

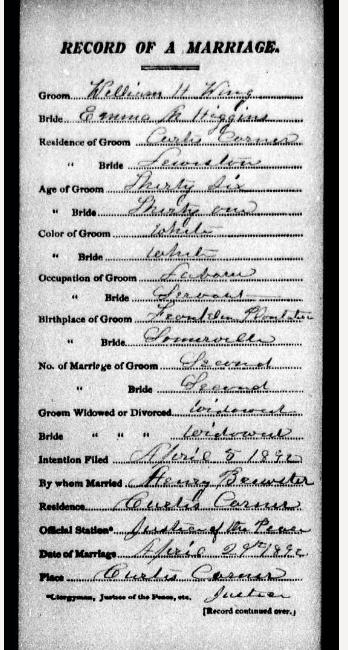

Emma Place (1859 – 1926), daughter of Abraham Place and Julia Light, had three husbands during her 67 years here on earth. The first one, Jame O. Higgins, died sometime between their daughter’s birth in 1886 and Emma’s second marriage in 1892. Emma’s second husband – so my 3rd-step-great-grandfather, but also my 1st cousin 4 times removed – was William Henry Wing (1856 – 1936), son of George Washington Wing and Nancy Canwell.

Unfortunately for these two widowed and remarried people, things did not seem to go well. After only 9 years of living together, Emma moved out of the home she shared with William. Two years after, she petitioned for divorce.

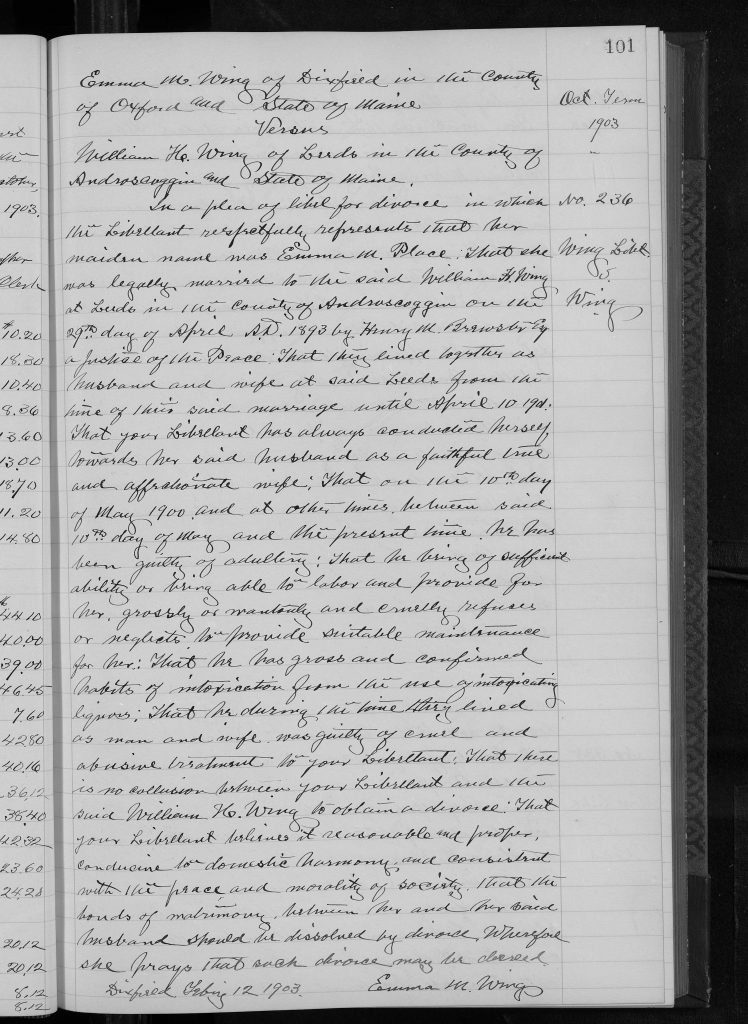

Below is a copy of the above image:

In a plea of libel for divorce in which the librelant respectfully represents that her maiden name was Emma M. Place, that she was legally married to the said William H. Wing at Leeds in the county of Androscoggin on the 29th day of April AD 1893 [1892] by Henry M. Browsby Esp a Justice of the Peace; That they lived together as husband and wife at said Leeds from the time of this said marriage until April 10 1901; That your librelant has always conducted herself towards her said husband as a faithful true and affectionate wife; That on the 10th day of May 1900 and at other times between said 10th day of May and the present time he has been guilty of adultery; That he bring of sufficient ability or bring able to labor and provide for her, grossly or wantedly and cruelly refuses or neglects to provide suitable maintenance for her; That he has gross and confirmed habits of intoxication from the use of intoxicating liquors; That he during the time they lived as man and wife was guilty of cruel and abusive treatment to your librelant; That there is no collusion between your librelant and the said William H. Wing to obtain a divorce; that your librelant believes it reasonable and proper, conducive for domestic harmony, and consistent with the peace and morality of society that the bonds of matrimony between her and her said husband should be dissolved by divorce, Wherefore she prays that such divorce may be decreed.

Dixfield Febry 12 1903

Emma M. Wing

In summary, William H. Wing was not a fantastic specimen of a husband. From what Emma states, he refused to work, had an affair multiple times, was constantly drunk, and abused her. Thankfully for Emma, her divorce was agreed to by a judge in October of 1903.

Emma was granted her divorce from William on the charges of cruel and abusive treatment.

All was not lost, though, for in 1905 Emma married her third husband, James Monroe Haynes (1856) and remained with him until his death in 1915. After that, she lived with her son John and later became caretaker of her grandson, Leo D. Wing, son of Carrie Higgins Wing, until Emma’s death in 1926.

This is just one or hundreds of divorces that took place in Maine during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Scanned records of divorces from 1892 to 1963 can be found at the Digital Maine Repository. Some indexed records from 1799 to 1908 can be found at Maine Divorce Records via Maine Genealogy.

As a fun little “bonus” piece to this spiel about Emma Place and her divorce from William H Wing, I’m going to include the following, very rough, concept map of the connections between Emma, her second husband, third husband, daughter, and son-in-law. It’s an interesting map and will probably show up in another post that I’m working on regarding Carrie Higgins, Emma’s daughter.

I’ve placed Emma in pink so that it’s easier to find her and trace around the map to the other people. It seems that Emma was destined to have some connection with the Wing family, one way or another.

This blog post is done in part for Amy Johnson Crow’s #52Ancestors challenge. To learn more, visit https://www.amyjohnsoncrow.com/52-ancestors-in-52-weeks/.