The Search for Julia – Part III

On 14 February 2022 by TRaymondAs I’ve shared in The Search of Julia and The Search for Julia – Part II, I’m on the hunt to find one of my 3rd great-grandmothers. She has been a brick wall in my research for a while now, and I figure sharing some of the tactics I use to try to scour out a loose brick to get past this obstacle might help others.

Thankfully, the #52Ancestors challenge has been lending itself well to this.

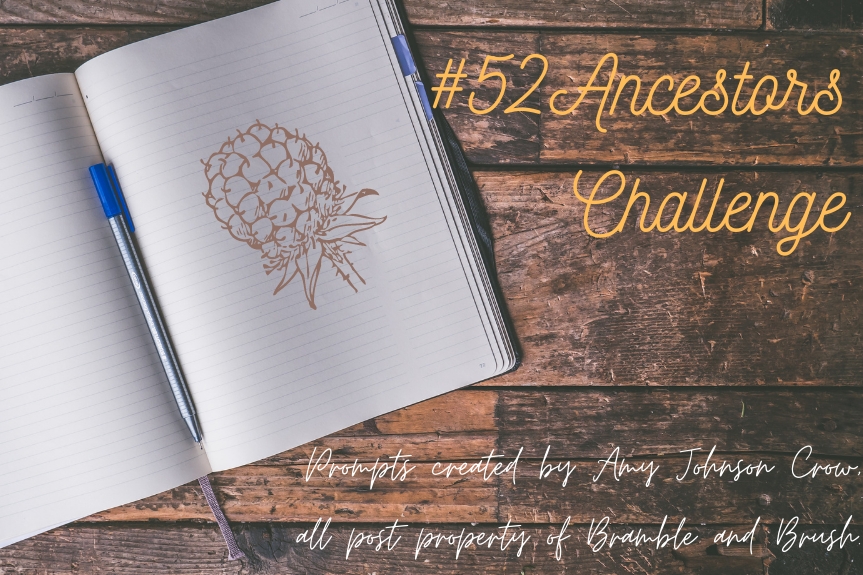

This post’s prompt is all about maps. Maps are something that many people tend to over look, especially as they can be few and far between in many time periods. One wonderful bonus about living in Maine, however, are the maps at the Library of Congress’ website. In the late 1850s and early 1860s, each county in Maine had a topographical map produced from survey data. Obviously, these maps aren’t necessarily without faults, but they give a great insight as to the people who lived in the towns and counties at the time.

- Androscoggin County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2012592363/

- Cumberland County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2012592364/

- Franklin County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2012592365/

- Kennebec County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2012592366/

- Lincoln County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2011589601/

- Oxford County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2012592367/

- Penobscot County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2012592368/

- Piscataquis County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2012592369/

- Sagadohoc County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2011589603/

- Somerset County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2012592370/

- Waldo County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2011589602/

- Washington County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2012592371/

- York County – https://www.loc.gov/item/2011588007/

One of the next steps for hunting down the possibly families of Julia Light will be a reverse crawl from these maps.

Given that most of Julia’s married, and most likely pre-married, life took place in Patrickstown Plantation, later known as Somerville, I started by finding the map for the town, in Somerset county.

By zooming into these maps through the Library of Congress’ interface, I can legibly read the names of the heads of households for the dwellings. This map is from 1857, a long ways after Julia Light was born in 1820, but the names on these maps can certainly give a few potential leads. By looking at anyone with the shared surname of Light living in any of the potential areas in which Julia was born or lived, I can begin crawling back up family trees to see potential connections. While I might not find a direct relation, sometimes even finding a first or second cousin can help lend light on the potential paternal family.

For example, in Washington, the town next door to Patrickstown Plantation, there are at least three homesteads with the surname of Light. These could be brothers, cousins, or uncles of Julia Light. If I can track these names down in the census data and then create a family tree for them going back two to three generations, this might generate some leads. (We all know that in a perfect world census data would be digitized without issue, but that world just doesn’t exist. These maps can give genealogists an idea as to what might be hiding in the census records that weren’t digitized correctly, or families that moved in and out between census records.)

For towns and cities that are more densely packed, the Library of Congress also has Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps that might be able to shed light in the search as well. Unfortunately, areas like plantations out in the middle of Maine aren’t really seen as needing insurance mapping during the time period that those maps were created.

This blog post is done in part for Amy Johnson Crow’s #52Ancestors challenge. To learn more, visit https://www.amyjohnsoncrow.com/52-ancestors-in-52-weeks/.

Active member of: