Welcome back to this space, loves!

So, it’s obviously been a while since I posted on here about anything genealogically related. As anyone will attest, life sometimes steers us more than we steer it.

Now that I’ve been able to take the reins back, I’m working on a few different projects. One of the most exciting ones deals with two families on my paternal line. Like many people whose families have been in the United States for generations, many of my relatives took part in the Civil War, including my 4th great-grandfather Willard Judkins and my 3rd great-grandfather Greenfield Preston Coburn. Willard’s grandson, Laforest Eastman Judkins, and Greenfield’s daughter, Lulu Mae, would grow up to marry one another and become my 2nd great-grandparents.

During the Civil War it was a common thing for all the sons of a family to join the armed forces, especially as volunteers. Willard and Greenfield’s families were no exception. What was interesting to me was the vast difference in the outcomes of the two families from the war.

Willard Judkins and his four brothers all volunteered for the service, leaving behind two sisters in the care of their parents. Only Willard and his younger brother Eastman would return. Brothers Orrin, Asaph, and Benjamin all died during the war. Sadly, the two sisters, Mercy Ann and Irene, would also pass during that time.

Greenfield Preston Coburn also had four brothers. The youngest, Wallace, was only 9 when the Civil War began and never saw battle. Greenfield’s brothers Jefferson, Hiram, and John all signed on as volunteers in the war. The three eldest sisters -Loretta, Angelia, and Ellen – were all married, but Sara and Ella Maria were still at home with little brother Wallace the their parents. Unlike the Judkins brothers, all four Coburn boys who saw action returned home.

My goal is to piece out the stories of what happened to each family. From tracing what units the boys served in, to how they moved up through the ranks (if they did), I hope to find how it is that one family was dealt with the heartbreak of losing all two children during the Civil War, while the other, who were neighbors in the same town, saw their how family survive to see the end of the war.

When I first started looking into the Judkins side of my family, I realized that a lot of the family members were from Weld, so, naturally, I stared looking for the vital record for Weld, Maine, online. They were there, but they weren’t tagged, transcribed, or quickly searchable by any means. I decided if I was going to have to look through reams of images, I might as well transcribe them. I started making headway with the process, but somewhere along the way, I lost my link for the digital images I was working from.

Damn.

Well, I didn’t have the best form going into the Weld records, so let’s start again with a different town that I knew I’d have to dive into the vital records of someday. I decided to work on the records for Carthage, Maine, a little town right next door to Weld.

I am forever grateful that I did!

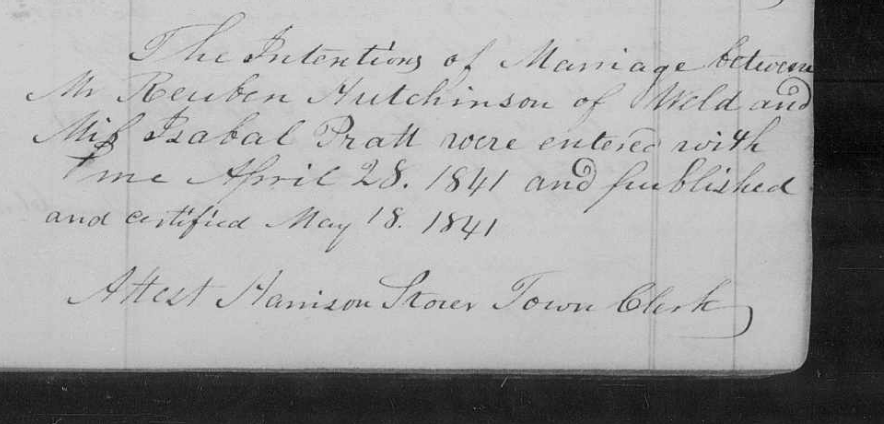

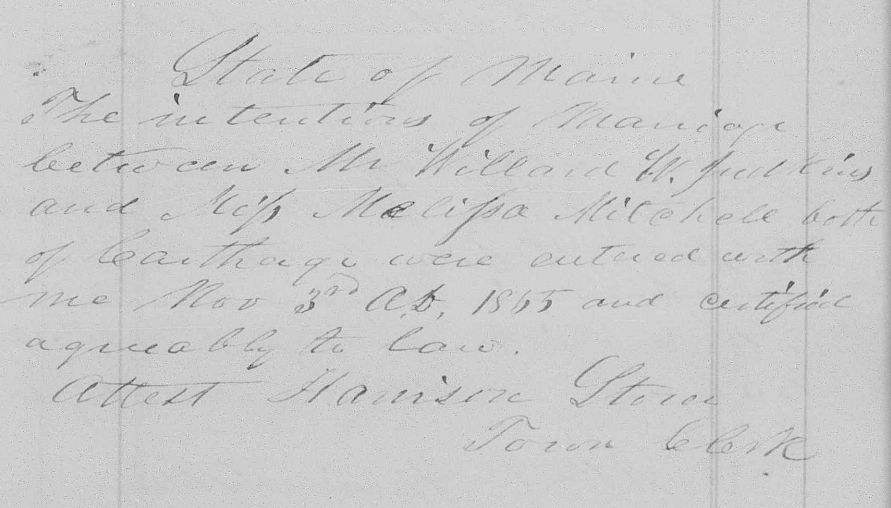

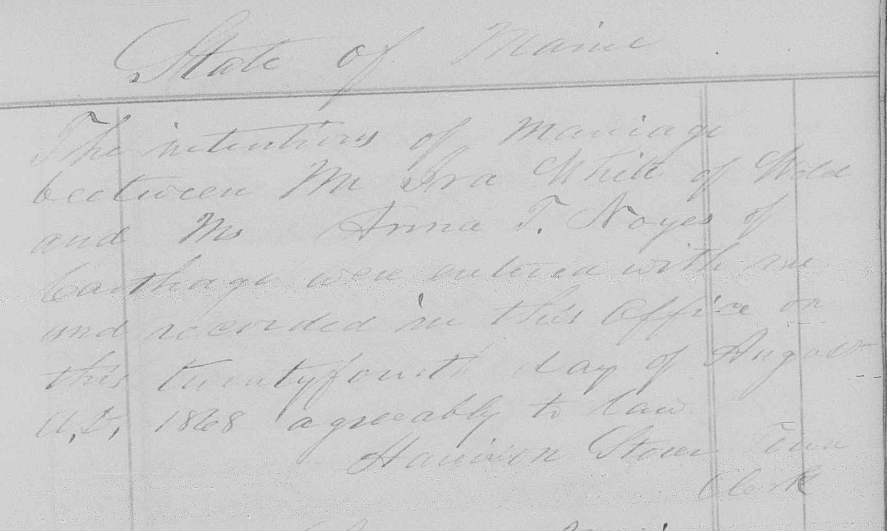

So far I have found intentions of marriage for:

My 4th great-grandparents, Reuben Hutchinson and Isabella Pratt;

Another pair of 4th great-grandparents, Willard Judkins and Melissa Mitchell;

And yet another set of 4th great-grandparents, Ira White and Anna Noyes.

I’m no where close to done and can’t wait to see what other gems I might be able to snag!

The 4th of July is upon us once again! A time when many start thinking about the actions of those who helped form this country. Research regarding soldiers of the Revolutionary War is akin to traveling through the woods by bread-crumb trail – the pieces are few, far away from one another, and sometimes are non-existent. The biggest impediment of sold Revolutionary War records comes from how peace-meal the army was at the time and how frequently people deserted due to illness, drunkenness, or lack of pay.

With the release of Lin Manuel-Miranda’s musical Hamilton, many people are beginning the search for ancestors that fought in the Revolutionary War in hopes that they may have served with Alexander Hamilton himself. While I can’t claim that my ancestors played such a part, I do know that I am related to a few fellows who served during the time period.

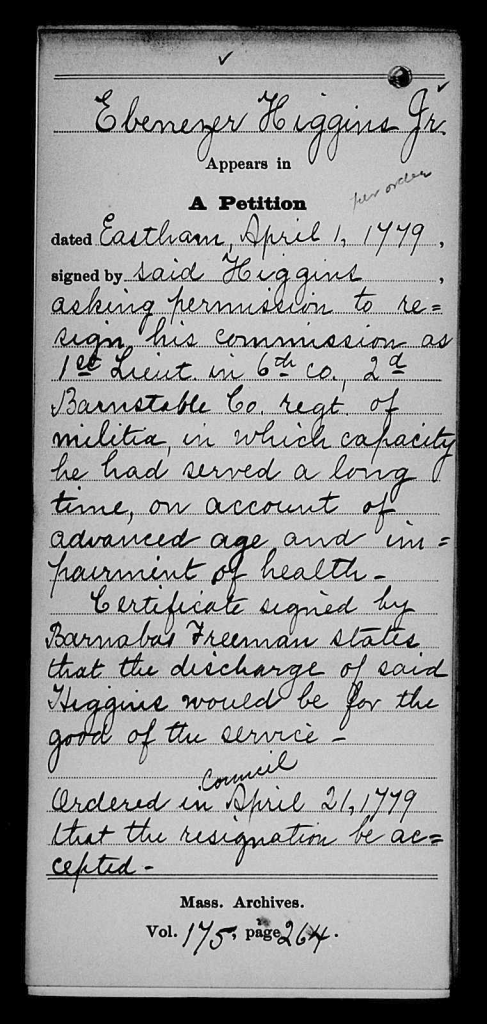

Ebenezer Higgins – 7th great-grandfather – Born July 21, 1721 at Eastham, Massachusetts,1 he served for many years as 1st Lieutenant in Capt. Elisha Doane’s 6th (2d Eastham) company of the Second Barnstable County regiment of militia. On April 26, 1776, Ebenezer was commissioned into active service at the age of 55 and served for another three years. It wasn’t until April 1, 1779, that he asked permission to resign on “account of advanced age and impairment of health.” Ebenezer’s resignation was officially accepted on April 21, 1779, and the age of 58 years.2

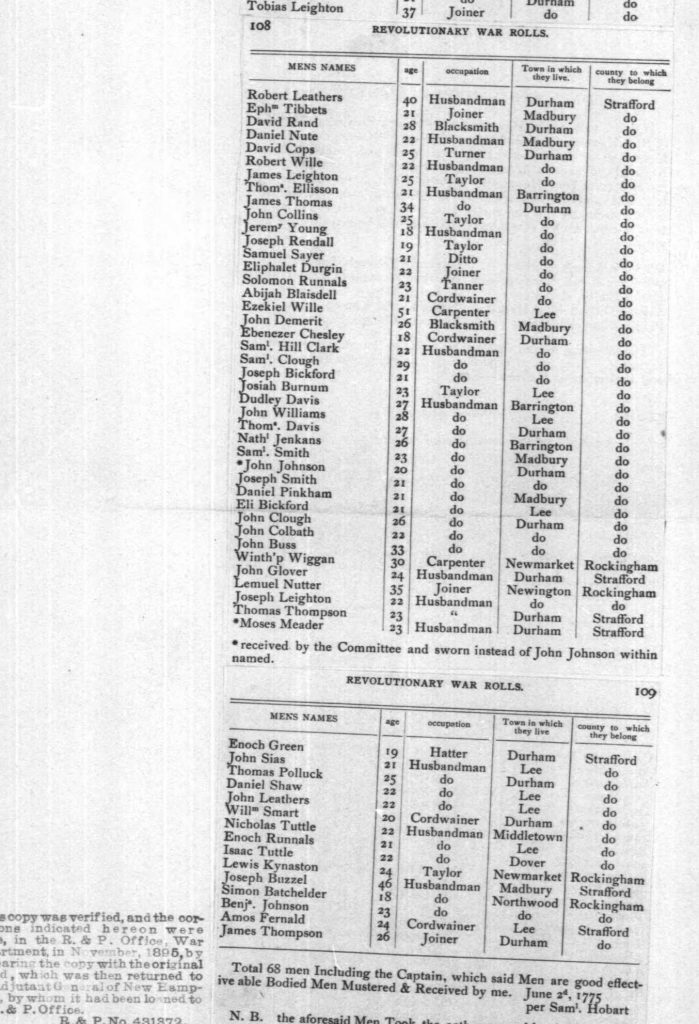

Source: US Revolutionary War Rolls, 1755 – 1783

Moses Meader – 6th great-grandfather – Born January 28, 1752, in Alton, New Hampshire,3 Moses entered into the Revolutionary War at age 23 in place of John Johnson. Moses served as a private under Captain Winborn Addams’ company in Colonel Enoch Poor’s regiment.4

Photo Credit: SacredCat

Philip Judkins – 7th great-grandfather – Another New Hampshire native, Philip was born on August 29, 1748.5 He was a soldier in the company of Jason Wait, part of 1st New Hampshire regiment. Shortly before the end of the battle at Valley Forge, Philip was busted from Corporal back to Private,6 and additionally was written up for desertion twice, at least, once in 17797 and again in 1780.8 He is one of the few soldiers I found who used his own pension for his own needs – Philip lived to be 103 and most likely needed that pension to help cover his own costs of living while residing with family.9

Stephen Gardner – 6th great-grandfather – and Stephen Gardner Jr – 5th great-grandfather – While there are no records of either Stephen doing anything more than helping guard the shores of Dorchester, this “minor” action shows how common it was for the militia to help during the Revolutionary War in protecting the coastline.10

My search for Revolutionary War patriots on my lineage is far from over. Aside from these five men, there is the distinct possibility that the following ancestors may also have served during this time:

Ebenezer Andrews

Ebenezer Andrews Jr

Reuben Wing, Sr

Joseph Wing

Steven Landers

Jacob Quimby

Samuel White

1 American Genealogical-Biographical Index, database, Ancestry.com

2 US Revolutionary War Rolls, 1755 – 1783, database, Ancestry.com

3 New Hampshire Births and Christenings Index, 1714 – 1904, database, Ancestry.com

4 Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War, compiles 1894 – ca 1912, documenting the period 1775 – 1784, roll 0522, image fold3.com

5 Maine Faylene Hutton Cemetery Collection, 1780 – 1990, Ancestry.com

6 Entry for Philip Judkins, ID# NH20759, http://valleyforgemusterroll.org/

7 New York Historical Society (1916), The John Watts de Peyster Publication Fund Series vol 47, pg 312

8 New Hampshire (Colony) Probate Court (1874), Provincial and State Papers Vol. 8, pg 852

9 Maine Faylene Hutton Cemetery Collection, 1780 – 1990, Ancestry.com

10 Massachusetts Office of the Secretary of State (1896), Massachusetts soldiers and sailors of the Revolutionary-War – a compilation from the archives, pg 278

As with all written pieces of genealogical research, the findings in this piece are subject to change based on new evidence as it becomes known.

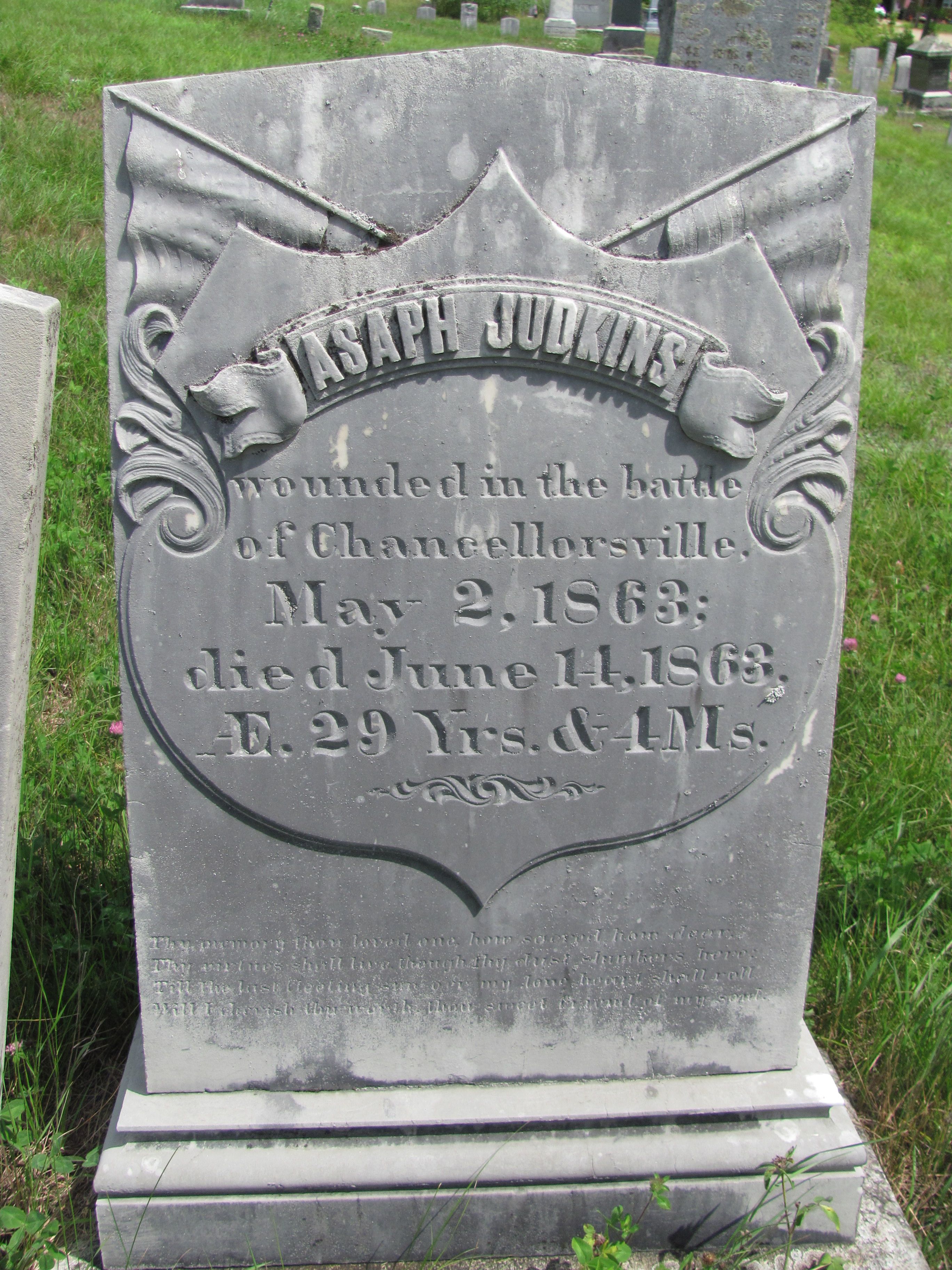

Photo credit: Gail Kelly

Growing up I always had a love for learning about the Civil War. It was an insatiable thirst which had no tangible reason to exist. Maybe it was because it was a war that held so much promise to bring our nation even closer together, to create a more just and stable union, a country for all people – and utterly failed. (If you don’t understand that last part, study the Antebellum years. A lot of schools in the US gloss over that and you’ll find out why.) Or it could have been that the war brought to a head the concept that a nation so large is bound to hold varying, and sometimes disastrously so, difference in morals and political views, an issue that still lingers. As a student, and now a parent, I feel that the Civil War is never studied deeply enough, especially when many of our nation’s current issues are rooted so tightly to the outcome and lack of follow-up from that war.

So, being partial to the time period of the Civil War, I tend to keep an eye out for family members that may have fought during the time. With Memorial Day drawing near, I felt it fitting to share one of the family stories that I have uncovered over the years.

Philip and Rachel (White) Judkins are my 5th great-grandparents. Married in Weld, Maine, on Dec 6, 18291, the Judkins had seven children born between 1831 and 1846.

i. Orrin Judkins b. 18312

ii. Willard W Judkins b. 1831

iii. Asaph Judkins b. 1834

iv. Irene Judkins b. 18363

v. Benjamin Judkins b. 1839

vi. Eastman Judkins b. 1840

vii. Mercy Ann Judkins b. 18464

Given the dates of birth, it’s easy to figure that at least one, if not multiple, of the brothers would be in the Civil War was a bit obvious. What was surprising it that all five of the Judkins brothers fought in the Civil War.

Orrin Judkins, the oldest brother, had moved out of Carthage early on. After marrying in Boston, he and his wife (Ellen Dinan)5, moved to Wisconsin6, where they were living when he mustered into Company B of the 23rd Wisconsin Volunteers. He left for the war leaving his four children and wife hoping for his return.7

Back in Maine, Asaph, who was living in Lewiston8 with his newly wedded wife in 18609, volunteered for service. He found himself in the Company H of the 10th Maine Infantry with his brother Willard.10 While Asaph and his wife had not yet had time to start a family, his brother Willard left wife Melissa with three boys to tend to and expecting a fourth.11

In 1860, the youngest two of the Judkins brothers, Benjamin and Eastman, were still living on the farm. they also signed up for the war. Eastman found himself in the same company as Asaph and Willard.12 Benjamin was placed in Company E of the 32nd Maine Infantry.13 Neither of the younger brothers were married.

Five brothers went into the Civil War. Only three came back.

Asaph, Willard, and Eastman all began in Company H of the 10th Maine Infantry as privates, but when the company was restructured after the leaving of some men mustered out, their company was changed to Company B. In the new Company B, Asaph and Eastman remained privates, but Willard was promoted to corporal.14 With all three brothers in the company, the ensemble arrived at Chancellorsville. On May 2, 1963, “strolling about at will, or lying under the trees, enjoying the delightful air and sunshine” (from History of the First-Tenth) when they were attacked by a rebel battery. Asaph, would had been sitting on the bank of the river, was severely wounded in his foot by a shell fragment. “Two men remained with him until he was taken in charge by some surgeon.”15 One can only imagine that these “two men” were Willard and Eastman, knowing how disastrous a foot injury could prove at that time. Unfortunately, Asaph developed gangrene from his injury and died June 14, 1863.16

Eastman and Willard would continue on with the 10th Maine until Company B joined on with the 29th Maine. Willard received another promotion and became a sergeant of Company F during his remaining time17, while Eastman remained a private in Company H.18 The brothers mustered out on January 11, 186519 and May 21, 1865,20 respectfully. They would be the only two of the Judkins boys to make it out of the war.

Orrin, the eldest of the Judkin brothers, passed away roughly a month before brother Asaph. While marching with Company B of the 23rd Wisconsin Infantry, the only unit he served with, Orrin was taken ill with “chronic diarrhea,” which more than likely was dysentery. Like many soldiers killed in the Civil War, his death didn’t come from a bullet. Orrin Judkins mustered out of the military due to death from illness on April 10, 1863,21 at Van Buren Hospital in Millikens Bend, Louisiana.22 His wife was left to fight for his pension, tend a farm, and raise four young boys on her own.23

Benjamin Judkins suffered a similar fate as his brother. As Company E and the rest of the 32nd Maine pushed had on the march to Cold Harbor, “the severity of the march, pursued with such rapidity beneath a burning sun, and along scorched and dusty roads, had exhausted the strength of some. And from this cause, there were losses by so-called “straggling”, as in many cases men who were worn out and wearied beyond the power of endurance, were unable to keep up with the swiftly-moving columns, and compelled to fall out.” It’s easy to imagine that many of these soldiers were not only exhausted, but were also malnourished and/or dealing will illnesses such as dysentery. While the 32nd Maine avoided conflict during this period, many of those men who fell out of line were captured by the Confederates, including Benjamin Judkins.24 It was recorded that Benjamin died in Libby Prison on June 30, 1865, from disease.25

In an unfortunate twist of fate, both daughters of Philip and Rachel Judkins also passed away during the time of the Civil War. Mercy Ann died at the age of 15 on January 3, 1862,26 unwed. Irene (Judkins) Whitney passed away on September 18, 1860,27 leaving behind a husband and two sons.

This blog entry was written as an expression of love and remembrance for those who have died in war.

To Orrin, Asaph, and Benjamin, I say a well belated thank you for your greatest sacrifice. May you rest in power and peace.

1 Maine Marriages, 1771-1907, database, familysearch.org.

2 New England Historic Genealogical Society; Boston, Massachusetts; Massachusetts Vital Records, 1911–1915, p. 156

3 Philip Judkins household, 1850 US Census, Carthage, Franklin Co., Maine, pg 37.

4 Philip Judkins household, 1860 US Census, Carthage, Franklin Co., Maine, pg 13.

5 New England Historic Genealogical Society; Boston, Massachusetts; Massachusetts Vital Records, 1911–1915, pg 1562.

6 Orrin Judkins household, 1860 US Census, Kendall, Lafayette Co., Wisconsin, pg 12a.

7 The National Archives, case files of approved pension applications of widows and other veterans of the army and navy who served mainly in the Civil War and the War with Spain, compiled 1861-1934, roll WC32884-JUDKINS-Orrin, image, familysearch.org.

8 Asaph Judkins household, 1860 US Census, Lewiston, Androscoggin Co., Maine, pg 99.

9 Maine Marriages, 1771-1907, database, familysearch.org.

10 Gould, M. J. M., & Jordan, R. L. G. (1871). The History of the First-Tenth-Twenty-Ninth Maine Regiment in Service of the United States from May 3, 1861, to June 21, 1866. Portland: Stephen Berry. pg 328.

11 Willard Judkins household, 1870 US Census, Carthage, Frankly Co., Maine, pg 8.

12 Gould & Jordan (1871), pg 328.

13 (Benjamin’s Unit list)

14 Gould & Jordan (1871), pg 379

15 Ibid., pg 343-344.

16 Ibid., footnote, pg 344.

17 Ibid., pg 627. Mistakenly recorded as “William Judkins.”

18 Ibid., pg 631.

19 US Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865, database, Ancestry.com.

20 Ibid.

21 US Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865, database, Ancestry.com.

22 US Registers of Deaths of Volunteers, 1861-1865, pg 51.

23 The National Archives, case files of approved pension applications of widows and other veterans of the army and navy who served mainly in the Civil War and the War with Spain, compiled 1861-1934, roll WC32884-JUDKINS-Orrin, image, familysearch.org.

24 Houston, Henry C., (of Co. C). (1903). The Thirty-Second Maine Regiment of Infantry Volunteers – A Historical Sketch. Portland, ME: Press of Southworth Brothers. pg 258-259.

25 US Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865, database, Ancestry.com.

26 Gravestone photo, Newman Cemetery, Carthage, Maine, findagrave.com #183851098.

27 Gravestone photo, Newman Cemetery, Carthage, Maine, findagrave.com #183791232.

As with all written pieces of genealogical research, the findings in this piece are subject to change based on new evidence as it becomes known.